From foreign domination to Estonian nationalist sentiment

Lydia Emilie Florentine Jannsen, poet and prose writer, known as Lydia Koidula, was born on December 24, 1843, in Vana - Vändra, Estonia. His father, Johann Voldemar Jannsen, authored the lyrics of the current national anthem of the Republic of Estonia and founder of the Pärnu Postimees and Eesti Postimees. Lydia is known in the history of Estonian Literature as a lyric poet. Author of several collections of poems, she reached her artistic peak between 1860 and 1880. She sought, with her poems, to awaken national consciousness and the unity of the Estonian people. Many of these poems became popular songs over time.

Estonia is a country located in Northern Europe, bordered by the Baltic Sea and bordered by the Gulf of Finland. From the 10th century onwards, Scandinavian Vikings advanced through the region and ushered in a period of intensification of foreign occupations in the Baltic countries, including Estonia. The country passed under the rule of Danes, Catholic orders, Swedes, Germans and Russians.

The Germans invaded Estonia in the 13th century and came into direct conflict with the Vikings. German rule extended until the 16th century. Latvia and Estonia formed the Livonian Confederation. With the end of the confederation, Estonia was incorporated into the Swedish Empire, which now encompassed much of the Baltic region.

While a rich folk culture of songs, fairy tales, proverbs and riddles flourished in the villages, there was still no Estonian literary language and literature. The urban intelligentsia was under strong German and later Russian influence. Poverty and ignorance roamed the countryside, while foreign languages and traditions took over Estonia's cities.

Inspired by traditional Estonian folklore and Kalevala, Finland's Friedrich Robert Fählmann (1798–1850) and Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (1803–1882), an Estonian physician and writer considered the father of national literature, spent three decades collecting legends, myths and old songs of your nation. At this point, Estonian intellectuals, influenced by the spirit of romantic nationalism, asked scholars to "give the nation an epic and a story; the rest would be earned".

From 1857 to 1861, encouraged by the Estonian Scholar Society, founded in 1838, Kreutzwald published the epic work in its final form of 18,993 lines under the title Kalevipoeg (The Son of Kalev, Father of Heroes). Powerful and agitated, Kalevipoeg ends with the prophecy that one day Kalev's son will be freed by fire from the rock that holds him prisoner, and Estonians will once again be a happy and prosperous people.

Period National Awakening in Estonia

When Koidula began publishing his works in the 1860s, the political and literary climate was quite authoritarian. Despite this, it was the moment of national awakening when the Estonian people began to feel national pride and to aspire to self-determination. Koidula was the most articulate voice of these aspirations.

The Era of Ärkamisaeg (Estonian Awakening) is a period in history when Estonians recognize themselves as a nation deserving the right to govern itself. This period begins in the 1850s, with greater rights being granted to commoners, and ends with the declaration of the Republic of Estonia in 1918. However, in 1940, the country was dominated by the USSR - Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The recovery of its sovereignty only happened in 1991, with the end of the USSR.

Movement Biedermeier

Biedermeier is the term by which a popular style became known in Germany and Austria, resembling a simplified imitation of the style of the French empire that preceded it. The movement lasted from 1815 to 1848. The term became derogatory because it designated an art valued as petty bourgeois taste, typical of the Germanic middle class of the first half of the 19th century. However, for many Germans this predilection was a virtue and symbolized sobriety, simple and domestic feelings.

In Literature, the term Biedermeier first appeared in literary circles in the form of a pseudonym, Gottlieb Biedermaier, used by rural physician Adolf Kussmaul and lawyer Ludwig Eichrodt in their work Fliegende Blätter (Flying Leaves), a collection of poems that the duo had published in Munich.

The patriotic poetry of Lydia Koidula

The most significant part of Koidula's creation is her patriotic poetry. The nationalist spirit that claimed the native culture and language in some lands subject to the Russian Empire was a very thorny issue at that time. However, in 1857, during the liberal reign of Tsar Alexander II (1855-1881), Lydia's father managed to convince the censorship and publish the Pärnu Postimees, the first Estonian-language daily newspaper that circulated until 1863. In the same year, he founded the Eesti Postimees whose content was similar to the previous one. Lydia helped her father edit both newspapers. In 1865, at the age of 22, and under the pseudonym L, she published her first poem entitled Koddo (House), at the Eesti Postimees.

In 1850, her family moved to a county near Pärnu, and in 1864 to the city of Tartu. Perhaps nostalgia for her homeland was what inspired her to write her romantic poetry. She constantly refers to her country and her people who for centuries lived in conditions close to slavery by Baltic-German barons.

In 1867, in the second also anonymous collection, called Emmajöe Öpik (The Nightingale of Emajõgi), she appears as a bard of the nation, whose romantically exultant verses expressed the feelings and thoughts of a nation awakening to a new life. Bard, in ancient Europe, was the person in charge of transmitting stories, myths, legends and poems orally, singing the stories of his people in recited poems.

Later, bards would be called troubadours. The musical and literary traditions that they passed on to successive generations gave rise to the songs of gesta. To play his music, the bard often used a lute, a stringed instrument, of Arabic origin, with a sounding board in the shape of a half pear and a long neck. Bards often told sad stories or epic poems, accompanied by lyres or harps.

The German influence on Koidula's work was inevitable. Baltic Germans held hegemony in the region since the 13th century. Throughout German, Polish, Swedish and Russian rule, German was the language of instruction and intelligentsia in 19th century Estonia.

The Estonian language as a communication tool in Koidula's works

The Estonian language remained the subject of orthographic disputes, still used primarily for predominantly paternalistic educational or religious texts, practical advice for farmers, or cheap, light-hearted folk tales.

Therefore, the importance of Koidula's poetry is not in the type of poetic verse, but in the unbridled and explosive use of the Estonian language, as a means of emotional and poetic discharge. She has successfully used the vernacular to express emotions ranging from an affectionate poem about the family cat in Meie kass (Our cat) to a delicate love poem Head ööd (Good night) to the vindictive Mo isamaa, nad olid matnud (My country, they buried it). With Lydia Koidula, the colonial view that the Estonian language was an underdeveloped instrument of communication was demonstrably contradicted.

Pioneer in Estonian dramaturgy

In Estonia, in the early 19th century, theater was not appreciated and many writers considered dramaturgy and theatrical art of little importance, even though Kreutzwald translated two tragedies into verse.

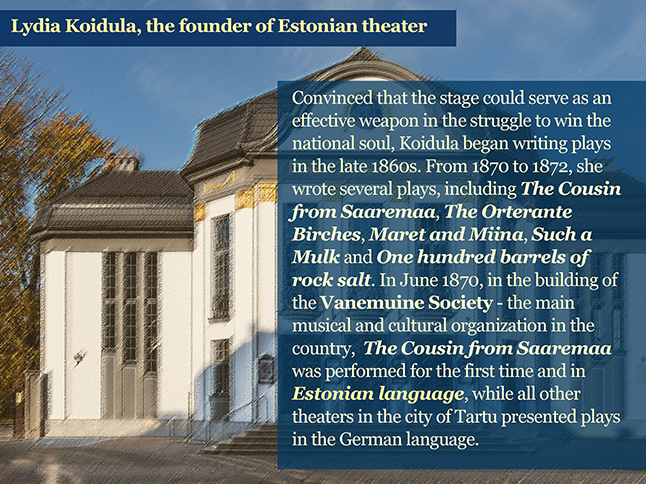

In 1865, in Tartu, the Jannsens founded the Vanemuise Selts (Vanemuine Society) with the aim of promoting Estonian culture. Lydia was the first to write original plays in Estonian and to tackle the practical aspects of stage direction and production.

In the late 1860s, both Estonians and Finns began to develop work in their native languages. Koidula wrote and directed, for the Vanemuine Society, the comedy Saaremaa Onupoeg (Saaremaa's Cousin) at Midsummer 1870. The play, considered the beginning of Estonian-language theater, was based on the farce by Theodor Körner Der Vetter aus Bremen (The Cousin of Bremen), adapted to an Estonian situation. The characterization was rudimentary and the plot simple but popular. That is why Lydia Koidula is considered the founder of Estonian theater.

Koidula's relationship with the theater was influenced by the philosopher Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (German playwright, philosopher and art critic, considered one of the greatest representatives of the Enlightenment, also known for his criticism of anti-Semitism and defense of free thought and religious tolerance). He was the author of the play Erziehung des Menschengeschlechts (The Education of the Human Race, 1780). His works considered didactic were a vehicle of popular education.

Koidula's theatrical resources were rare (inexperienced actors, amateurs and women played by men), but what impressed his contemporaries was the gallery of believable characters and knowledge of contemporary situations. Much smaller in scale, but pioneering, is the dramatic work created by Koidula and his activities in establishing the Estonian stage.

Her plays, modest and simple under the circumstances, initiated a veracity in people's lives and idealistic thinking on the Estonian stage, which is why they were repeatedly performed in later years.

Biography

Lydia Emilie Florentine Jannsen was born on December 24, 1843 (although some biographies indicate that she was born on December 12), in the town of Vana-Vändra, County Pärnu, in the former province of Livonia. She was the daughter of political and cultural activist Johann Voldemar Jannsen, founder of Pärnu Posttimees, the first Estonian-language newspaper, in 1857, and of Eesti Postimees, in 1863. He also authored the lyrics of the current national anthem of the Republic of Estonia: Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm (My native land, my happiness and joy', 1869). Her mother was German and little is known about her.

In 1850, her family settled in Pärnu, where she studied at a German girls' school (1854-1861), and in 1862, she successfully passed the University of Tartu exam and obtained a tutor's diploma.

In 1863, the whole family moved to Tartu (Dorpat at the time), the most liberal city in Estonia. In 1869, Johann Voldemar Jannsen was the key person in the beginning of the Lalupidu song festival tradition. Bringing together choirs from all over the country, the festival has become the most important cultural event for Estonians and a fundamental support for their conscience as a nation.

In 1873, Lydia married Edward Michelson, a Latvian student at the University of Tartu. They moved to Kronstadt, where he worked as a military doctor. In 1874, their first child, Hans Waldemar was born; two years later a daughter, Hedwig, was born, and in Vienna, a second daughter, Anne, was born in 1878. Between 1876 and 1878, the Michelson family traveled to cities such as Wroclaw, Strasbourg and Vienna. A cancer victim, Lydia died in Kronstadt, near Saint Petersburg (Russia), on August 11, 1886.

No comments:

Post a Comment