The relentless pursuit of fame

In the previous post, we talked about Marie Bashkirtseff's relentless pursuit of fame and posterity. We made a brief introduction about her Journal and the last moments of her life. I do not capitulate, she once wrote, in the face of the evil that would take her to the grave.

At the moment when a new female model emerged - the one that women today support, to inaugurate the rebellion against a world dominated by men who instituted marriage as their only destiny, the reading girls were amazed by the struggles of this fragile young woman who she fought her crusades lamenting the female condition of her century. Narcissistic, yes, but overloaded with self-love, she accepted all the challenges and worked tirelessly to be great among the great and thus knew how to inflate the hearts of her readers with self-esteem.

The first edition of the Journal, a summarized and censored view of the manuscripts

After the writer's death, her mother

fulfilled her will. From an editorial point of view, there was a material

impossibility of printing the Journal in its entirety. For the task, her mother

had the support of the prestigious poet, novelist and playwright André

Theuriet. The result of this partnership was an edition that, in addition to

being a summary, ended up being a mutilation.

Published

in France in 1887 by the publisher Fesquelle for the Bibliothèque Charpentier

collection. The two volumes, however, represented only about 20% of the manuscripts

left by the writer. Considering that, she wrote daily, there were repeated gaps

that involved weeks and months. Characters that are fundamental to the

understanding of both the author's personality and her behaviors have

completely disappeared.

Even so, it was an unusual bestseller.

Not all the layers of that cosmetic could hide what was essential in the text

that held its readers.

Other publications around the world

The Journal soon began to be reproduced in different languages of the

world and the echo of his voice was heard in metropolises as far away as Tokyo

or Buenos Aires; also in the United States and the rest of Europe, for more

than half a century, young women read those pages with ardor to venerate her

life and deplore her tragedy.

In the twilight of a dark century in

which girls only learned to speak from their hearts, Marie spoke from her body.

Pierre-Jean Remy, French writer, prologue to the full version of the Journal

published by Marie Bashkirtseff's Cercle des Amis (Circle of Friends).

In

1925, five years after Madame Bashkirtseff's death and thirteen years since she

deposited the original manuscripts in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

(1912), a clause prevented their publication until 1930. However, Pierre Borel,

a minor writer, began to publish a series of volumes with unpublished texts

from the Journal:

Marie Bashkirtseff's Cahiers Intimes Inédits (Marie Bashkirtseff's unpublished intimate

notebooks);

Les Confessions de Marie Bashkirtseff (The Confessions of Marie Bashkirtseff);

Le Premier et le Dernier Voyage de Marie Bashkirtseff (Marie Bashkirtseff's First and Last Voyages);

La Véritable Marie Bashkirtseff (The real Marie Bashkirtseff), and probably a few

more.

A new Marie Bashkirtseff appeared: the

cerebral and ethereal version of Theuriet was contrasted with this other,

passionate, impetuous, sometimes reckless and often brutal, to the resounding

bewilderment of her readers.

Pierre Borel has long been a hero to

students of the life of Marie Bashkirtseff. However, although a profusion of

censored texts from that first edition appear in these books, the real Marie

Bashkirtseff remained unknown.

We are now convinced that Borel never

worked with the original manuscript, but probably with that copy that Madame

Bashkirtseff and her niece Dina had executed in the late 1880s, in short, also

a censored text.

Following decades

In the 1960s, she fell into oblivion,

precisely because for those women who freed themselves from concealment and

prejudice, her innocent image submerged her in the shadows. Her status as an

aristocrat, when it had already fallen into obsolescence, did not favor her

either. With few exceptions, readers and editors have turned their backs on

her.

Even

so, Doris Langley Moore found the original manuscript of Marie Bashkirtseff's Journal

in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and from there extracted material for

her book Marie and the Duke of H.: The Dreamy Love Story of Marie Bashkirtseff.

In 1985, the female Professor Colette Cosnier, a

great biographer of great forgotten women, published a magnificent illustrated

biography: Marie Bashkirtseff. Un

portrait sans retouches (A portrait without retouching), after reading the

entire monumental original manuscript of the Journal, deposited in the National

Library of France.

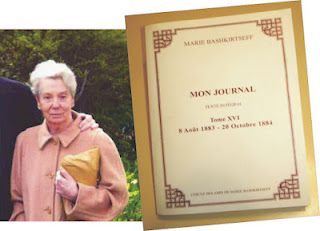

Since 1995, Marie Bashkirtseff's Cercle des Amis had been publishing another complete version of Marie Bashkirtseff's Journal. With transcription of the original manuscript by Cercle's Alma Mater, Madame Ginette Apostolescu, the edition was completed in 2005, with sixteen volumes of about three hundred and fifty pages each.

In

1999, a supposedly complete version of the Journal appeared under the publisher

L'Age de l'Homme. Lucile Le Roy was responsible for the transcription and

extensive investigative work, which resulted in an excellent, abundantly

annotated edition. Unfortunately, of the five projected volumes, only the one

that should have been the third appeared and which covered only three of the

twelve years of annotations.

In the 1970s, American female professor Phyllis Howard Kernberger began translating the Journal into English, using microfilms of the original manuscript that she had requested from the BNF. Her daughter, Professor Katherine Kernberger, inherited her passion and continued the work by publishing, in 1997, the first volume of the Journal, in English. In 2013, the second and final part based on the Cercle des Amis edition.

Who, after all, was Marie Bashkirtseff?

Gifted with many innate talents, how

many other pursuits would she be interested in if the ghost of a short life or

death itself had not crossed her path? When we read about her life and work,

what moves us is the tragic character of her existence, in the classic sense of

the term: the death of the hero.

People, back then, used to have time, that

is the first thing that comes to mind. Yes, she had time, rich, as she was

lucky enough to be born. Yet she might as well have devoted herself to the same

thing as the vast majority of her classy girls, to be idle, simply waiting for

a husband.

She could also have excelled in other

activities, her singing career, interrupted by chronic pharyngitis. Moreover,

in music, especially the piano, to which she devoted many hours a day for many

years until she reached mastery. She mastered the harp, the guitar and the

mandolin and in her last days considered herself capable of composing.

On top of all that, he squandered his

creativity on haute couture. She designed her own dresses and was a fashion

reference in Nice and Paris, imposing her style so that the big fashion houses

ended up copying it. When the selfie did not yet exist, she had the lucidity to

be photographed hundreds of times throughout her existence to illustrate her Journal.

A girl today!

Did the edition of the Journal

influence her notoriety as a painter? Maybe a little. However, a few years

before her death, the public and critics had already recognized her talent. The

French state acquired his Encounter canvas for the Luxembourg museum two years

before the Journal appeared.

Was her feverish work, her meteoric

career in painting, due solely to the perception of an approaching death? Well,

she herself confessed that since she was a little girl, she felt called to

become an exceptional being, something that in her early years she identified

with royalty or the lights of the stage.

The consciousness of a short life made

her discard a path in literature or journalism, activities for which she knew

she was naturally gifted. How far would this woman of our time have come if she

had been born in our time?

Used and suggested links

He discovered Marie Bashkirtseff as a

youth in Buenos Aires in the 1970s, reading the Journal, a yellowed edition he

found in one of the many legendary second-hand bookstores on Avenida

Corrientes.

No comments:

Post a Comment