Ecstasy and envy provoked in Virginia Woolf

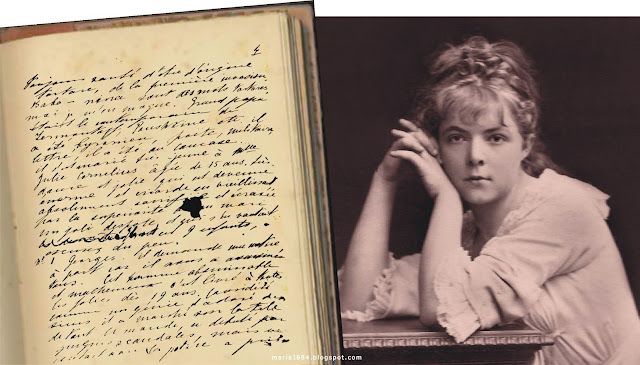

Kathleen

Mansfield Beauchamp, original name of Katherine Mansfield, was born in

Wellington, New Zealand, on October 14, 1888. She spent her childhood in

Wellington, and then traveled to London in 1903 with her two older sisters to

attend Queen's College.

But this book is me!

Clarice

Lispector, one of the most important Brazilian woman writers, was another great

writer of the 20th century who recognized the power of Katherine Mansfield's

writing. Reading the work of the New Zealander for the first time, Clarice

would have said that Mansfield was herself. The “Clarice Lispector of the

English language” is perhaps a good way to introduce this brilliant author to

the Portuguese-speaking audience. There are many common points between them –

the literary work from the perspective of the woman, the contemplation of

everyday life, human relationships, and the intelligent use of silence.

Clarice

discovered Mansfield's work alone when she took the collection Bliss from a

bookstore shelf. Not knowing who it was, she started reading right there,

standing up, and could not stop, taken by a deep affinity with the author: “But

this book is me!” she would have thought in the face of the volume of short

stories she acquired.

The unhappy translation of Bliss as happiness

The

Brazilian writer Érico Veríssimo was the one who translated Bliss in

Brazil, in 1940, by Editora Globo. However, he was unfortunate in translating

Bliss into Happiness. Ana Cristina Cesar, a Brazilian female poet and translator, seems to have

hit the target when she chose the term Ecstasy. Bliss is ecstasy, happiness,

joy, rapture, divine thing, palpitation, enchantment, enthusiasm, fascination…

Ana immersed herself in Mansfield's letters and diary while working on Bliss's annotated translation, which earned her a master's degree in Theory and Practice of Literary Translation from the University of Essex, England. The reading made the Brazilian poet realize that in Mansfield's work, as in her own, “fiction and autobiography constitute a single and indivisible composition”.

Her tales and her writing technique

Considered

a central figure in British modernism, her tales are innovative,

accessible and psychologically acute, pioneering the genre's form in the 20th

century. They are also notable for their use of stream-of-consciousness. She

described trivial events and subtle changes in human behavior.

Her

fiction, poetry, diaries and letters cover a range of subjects: the

difficulties and ambivalences of families and sexuality, the fragility of

relationships, the complexities and insensitivities of the rising middle

classes, the social consequences of the war and, above all, the attempt to extract

any beauty and vitality from the mundane experience. Thus, she rejected the

conventions of highly plotted narrative with a carefully crafted conclusion,

using direct and indirect narrative and a rapid transition of times to provide

constant shifts in perspective.

Her

characters do not stay in the spotlight; she just shows the inner life of each

of them. Looks, words, facial expressions. Many subjects cross her prose:

conversations about dreams and the intimates of the mind, typical of a society

that was awakening to the power of the Freudian unconscious. In particular,

women who constantly question their places in society. In all writings, critics

find an enormous depth of observation; a simple expression of what is

untranslatable in the human soul and a complex femininity surprising the

strange roots that held it to life.

She carefully manipulated the autobiographical element in her work. Art always transcended reality, and events or people remembered were molded to suit the impression she wished to convey. Her enduring appeal is perhaps due in part to the fact that at the best of her writing, fiction or nonfiction, she communicates her individual experience in such a way that different readers can identify with her.

Writing is

converted into a fictional exercise. With this, the writer establishes her gaze

on things, shapes sensations caused by people and places, reveals herself and

others. Literary activity is the main reason for her reflections in her diary

and letters.

A wandering and disordered life

Back at her

father's house, in 1906, at the age of 18, she came unhappy, bad-tempered and

rebellious. Wellington was a province for a young woman, already somewhat

disordered, after two cases of lesbianism, an obscure incident with a sailor

and the death of her beloved grandmother. In 1908, she convinced her father to

let her return to London. In July of the same year, she left New Zealand. She

carried a lot of material in her head that she would later use in her stories.

In London she would live, according to one of her biographers, “a wandering and

disordered life”.

Her first year was a disaster. When she was a student at Queen's College, she had an affair with Arnold Trowell, a young cellist. On her return to London, this love had cooled and he was transferred to his twin brother, Garnet Trowell. She continued to correspond with Arnold and formed a close friendship with a tall, awkward young woman, Ida Baker, whom she renamed Leslie Moore or LM, with whom she had, it is said, a passing love affair.

Her relationship with Garnett resulted in an unexpected pregnancy and she inexplicably became engaged to George Charles Bowden, a singing teacher. They were married on March 2, 1909 at the Paddington registry office, dressed in black, with Ida Baker as a witness. She left him on their wedding night, sexually disgusted. All this in just three weeks.

Ida Baker recounts that in early 1911, her friend apparently thought she was pregnant and wrote to Garnet several times, but with no response. In April 1911, LM opened a bank account to help her with the baby. After that, LM sailed to Rhodesia to visit her father. Back five months later, Baker found "no babies and a closed bank account." They never discussed the matter.

While

doubts have been cast on the veracity of this version of events, it may be that

some experiences in late spring 1911 contributed to the ambivalent views of

relationships and childbirth that are evident in her work at this time and in

later stories such as This Flower.

Six lonely months in Germany

Alarmed by

these developments, her mother, Annie Beauchamp, traveled to England and

immediately took her to the spa in Bad Wörishofen, Germany, for treatment and

childbearing. She left it there, promising to forget about it for the rest of

her life! Moreover, that is what she did.

In Bavaria,

Katherine suffered a miscarriage, although there are doubts about her pregnancy.

The six solitary months in Germany were the basis for the stories published in

1910 and 1911 in the literary periodical The New Age, edited by AR Orage. Many

of them have a young narrator, and usually, the female characters are alone,

vulnerable and naive, questioning their role in society and the double standard

that allows men to enjoy sexual pleasures while women suffer the consequences.

Upon

returning to London, Mansfield became ill with an untreated sexually

transmitted disease she contracted from Floryan Sobieniowski, a Polish émigré

translator she met in Germany. This contributed to her poor health for the rest

of her life.

John Middleton Murry, her second husband and future editor

In 1911, she met Oxford student John Middleton Murry, editor of Rhythm magazine, writer and socialist. At her invitation, he became her tenant, then her lover.

The next two years were important for Mansfield's growth as a writer – she published several New Zealand-themed stories – but there were constant financial worries and frequent changes of address. Together they edited Rhythm and Blue Review, but they could not avoid Murry's bankruptcy, which followed his stay in Paris at the end of 1913. It was only after 1917, faced with the profound shock that the First World War brought him, with the death of her dear brother, that her true genius would manifest itself in all its breadth with the tale Prelude.

After divorcing

her first husband in 1918, Mansfield married Murry. In the same year, it was

discovered that she had tuberculosis. Their relationship was unconventional,

often tormented, and while their mutual consideration ran deep, they often

misunderstood each other's needs.

Increasingly,

Mansfield demanded unconditional love and attention, which Murry was often

unable to provide; it was LM who offered unquestioning devotion and practical

support. For the rest of Mansfield's short life, Murry and LM were indispensable

to her, but for different reasons.

Mansfield

and Murry often lived apart for long periods, but corresponded faithfully. In

addition to writing hundreds of letters, partly as a substitute for

conversation, Mansfield filled notebooks and notebooks with thoughts, feelings,

draft stories, observations, and ideas.

Intense literary production, despite illness

Her first

tuberculous hemorrhage took place in February 1918. So began his race against

time: How unbearable it would be to die – to leave 'remains', 'pieces'...

nothing really finished. Although her tuberculosis was worse, she refused to

enter a sanatorium. Instead, in September 1919, at the beginning of the English

winter, she moved with LM to Ospedaletti, an Italian commune in the Liguria region

of the province of Imperia. Her disappointment at Murry's passivity and

apparent reluctance to support her led her to write The Man without a

Temperament in January 1920.

Mansfield

moved again in May 1921 to Switzerland. Murry gave up the editorship of the

Athenaeum to take it. At Chalet des Sapins, Montana-sur-Sierre, she wrote some

of New Zealand's most famous stories: On the Bay, The Garden Party and The

Dollhouse. The first two were published in The Garden Party and Other Stories

in February 1922.

At that time, in desperation, Mansfield underwent painful radiation therapy in Paris. While there, she met James Joyce and wrote The fly. Tired, she traveled back to Switzerland, where she completed her latest story, The Canary, set in New Zealand.

Despite the

advanced state of his tuberculosis, Mansfield planned another series of 12

connected stories that would form the main section of a new book, thus becoming

the third part of the story that began with Prelude and continued into At the

Bay.

Healing the Soul, Not the Body

Influenced

by mystical thinkers like PD Ouspensky, she was convinced that in order to

regain health and fulfill her ambitions, she should try to heal the soul, not

the body. She was determined to write stories free of cynicism, to lead a new

kind of life, to become A child of the sun. In October, she entered

GI Gurdjieff's Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at

Avon-Fontainebleau, near Paris. Her last letters to her family, LM and Murry,

show that in that community she finally found something of the resolution she

was looking for.

Murry

visited her on January 9, 1923. That same night she died of a pulmonary

hemorrhage, aged 34, at the Gurdjieff Institute near Fontainebleau, France. Her

last words were, “I love the rain. I want the feel of it on my face.”

Posthumous publications

Katherine left her manuscripts,

notebooks and letters to her husband for his disposal, with a request that he

"let it all be fair". In what was seen by some as a betrayal of that

trust, Murry used his papers selectively to compile the journal of Katherine

Mansfield in 1927.

In 1939, he selected more material

from the same sources to produce The Scrapbook of Katherine Mansfield, and in 1954,

he published an expansion, called the 'definitive edition'. He also published

two volumes of Katherine Mansfield's Letters in 1928, and Katherine Mansfield's

Letters to John Middleton Murry, 1913-1922 in 1951.

Ironically – for Mansfield had

described himself as “a secret creature to my very bones” – his most private

comments and musings, the diary, letters, and scrapbook were edited by her

husband, who ignored her desire for him to “tear and burn as much as possible”

the papers she left behind. However, the husband, managing his wife's work, has

been censoring excerpts from her diary and entire letters from her

correspondence, trying to erase any “negative” images from Katherine's life.

There was a double irony, for Murry's careful editing gave the impression that she was impeccable; by February 1923, she was already being described as "the holiest of women". Murry managed to create a cult of personality, and this no doubt contributed to the growth of Mansfield's international reputation after her death. He understood that the writings she left were very spontaneous, the most vivid, the most delicate and the most beautiful, that the English could read at the beginning of the 20th century.

Katherine

Mansfield was a victim of tuberculosis, as were the Ukrainian Marie Bashkirtseff and the Japanese Higuchi Ichiyô . All of them, in addition to the

Brazilian Carolina Maria de Jesus, left their diaries.

Used and suggested links

.jpg)