Florence Onyebuchi “Buchi” Emecheta is committed to correcting stereotypes of Nigerian and African women, exposing their daily reality and the oppression of social norms. Her work questions, among other topics, the education of women, the valorization of motherhood as the only possible concern, the degrading violence of colonialism and the culture that delegitimizes their autonomy.

Buchi was born in 1944 in the Yoruba city of Lagos and spent most of his childhood in Ibuza, the land of his parents, Alice Ogbanje Emecheta and Jeremy Nwabudike Emecheta, who went to look for work in Lagos, but insisted on cultivating their Igbo roots in their two children.

Yoruba people

Yoruba is the name of one of the largest ethnic groups on the African continent. In fact, the term is applied to a collection of diverse populations linked together by a common language of the same name, histories and culture. The ethnic groups that live close to the Yoruba are the Fon, Igbo, Igala and Idoma.

Most Yoruba people live in the southwestern region of Nigeria. There are also important communities present in Benin, Ghana, Togo and Ivory Coast. Due to the slave trade, which was very active in the area between the 15th and 19th centuries, many traits of culture, language, music and other customs were disseminated throughout extensive regions of the American continent, especially Brazil, Cuba, Trinidad and Tobago and Haiti. Much of the black population in Brazil came from Yoruba lands.

The recent history of the Yoruba is marked by the emergence of the Oyo Empire at the end of the 15th century, which was built with the help of the Portuguese interested in local commerce. Lagos, by the way, the most important and populous city in Nigeria, located in Yoruba lands, received its current name from the warehouse built by the Portuguese, a reference to the city in the south of Portugal.

In the early 19th century, the Fulani invasion pushed the Yoruba to the south, where the cities of Ibadan and Abeokuta were founded. The British from 1901 onwards officially colonized most Yoruba areas, under a system of indirect government that mimicked traditional structures.

Nowadays, in Nigeria, the Yoruba are an important ethnic group, representing about one-sixth of the population. They are mostly Catholic, but a part also follow Islam and traditional worship. About 75% of men are farmers who live off what they grow. Women are usually in charge of selling part of the surplus in popular markets in cities. Some individuals own large cocoa farms whose work is done by hired labor.

In addition to formal authorities, in the cities, the Yoruba respect the “Oba”, temporal leader, who conquers his position in different ways, including inheritance, marriages, or by personal selection of the Oba in power. Each Oba is considered a direct descendant of the founder Oba of each city, usually aided by a council of chiefs.

The elaborate costumes, traditionally made of cotton, are a highlight of Yoruba culture. The most basic is Aso-Oke, in many different colors and patterns. The agbada is one of the typical male costumes, whose name in Brazil has become synonymous with a kind of uniform of a particular carnival block.

Igbo people

The Igbos (pronounced Ibos) are one of the largest African ethnic groups. The majority of the Igbo population is concentrated in Nigeria, dominating part of the south and west, with around 25 million inhabitants. They are also found in Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, Gabon, Liberia and Senegal. Currently, thousands of them reside in the United States. The oldest oral tradition claims that their presence, in the so-called Land of the Igbos, dates back more than 1500 years.

The sovereign cities of the Igbo

Many cultures in Nigeria have not developed into centralized monarchies. Of these, the Igbo are probably the most notable due to the size of their territory and the density of their population. Igbo societies were organized into self-sufficient villages, or federations of village communities, with a society of elders and associations of age groups that performed various governmental functions.

In 1967, supported by the French multinational Elf-Aquitaine, they declared the independence of the eastern region of Nigeria, forming the Republic of Biafra. There was widespread famine in the region and civil war that led to the defeat of the Ibos.

Biafra war

Nigeria became independent in 1960. It was formed by the reunion of the Ibo people with the Hausa people. The Ibos came from the province of Biafra, in the east of the country, and formed the elite of Nigeria. In general, they were the ones who had the best jobs and the best salaries. In a coup d'état in 1966, a group of Ibo army officers seized power. However, the new government was overthrown in a counter-coup and the Ibos were hunted down and massacred across the country.

Those who managed to escape fled to their home province and declared themselves independent. As the province of Biafra was oil rich, the government would not accept the separation. The result was the civil war from 1967 to 1970, which resulted in the death of approximately one million people, mostly Igbo. The province of Biafra surrendered. Then, it was annexed again to the territory of Nigeria.

Colonization of nigeria

The first settlers who arrived in the country were the Portuguese, around 1470, followed by other European countries. Over time, the predominance of the occupation of Nigeria was in the hands of the British, who took control of most of the region, creating a single colony.

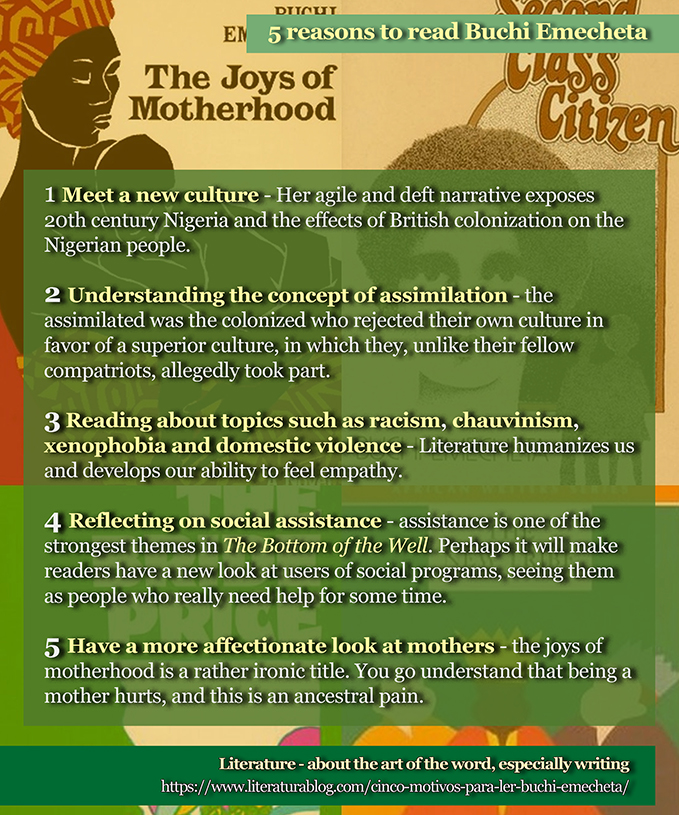

In the context of a class society, it was common practice for colonialists to garner support from the bourgeoisie and the local middle class, treating them as equals. In reality, the assimilated were the colonized people who rejected their own culture in favor of a superior culture to which they, unlike their countrymen, supposedly belonged.

Childhood and youth of Buchi Emecheta

As a girl, one of her passions was listening to stories from her elders. Accountants, following local tradition, were always someone's mothers. She grew up listening to her aunt, whom she called Big Mom. Buchi used to sit “for hours at her feet, mesmerized by his trance-like voice”, reveling in the process of her ancestors. The visits to Ibuza, combined with the pleasure and knowledge gained from the narratives, brought Emecheta the certainty that she would also be a storyteller.

During childhood, her brother, privileged to be a boy, went to school, while Buchi stayed at home. Later, after several insistent requests, she was enrolled in a mission school for girls, where she learned native languages and English – her fourth language.

Buchi Emecheta lived a rough childhood. However, poverty and malnutrition in her younger years, added to the early loss of her father when she was just eight years old, did not diminish her will to live, an intense desire that she would never abandon.

In 1954, Buchi received a scholarship to an elite school in Lagos. At that time, her mother passed away and she was passed from one distant relative to another. During school holidays, while her classmates returned to the comfortable homes of their families, she remained in the school dormitory, finding shelter in books and imagination. Coming back from vacation was her moment to shine, astonishing her colleagues with stories about supposed adventures.

Unhappy, abusive and violent marriage

At age 11, she met and became engaged to student Sylvester Onwordi, and by age sixteen, they were already married. Within the first few years, two of five children were born. The family moved to London and Onwordi went to the local university.

Emecheta lived an unhappy and often abusive and violent marriage. In her spare time, she started writing and had even developed the draft of a novel, which ended up being burned by her husband. He was consumed by an absurd sense of possession and was threatened by the will of his wife who dreamed of earning a degree and becoming a writer.

Buchi obtained a divorce in 1966, at the age of twenty-two. The ex-husband, however, did not acknowledge the paternity of the children. Penniless, with five children to care for and in a country foreign to her, she stubbornly maintained. She worked at the London Library while studying at night and began her writing career combining the education of her five children and studies at the University of London, where she obtained a BA in Sociology (1974), a Master's (1976) and a Doctorate in Education (1991).

Emecheta also worked at the British Museum in the 1960s, and served as a youth worker for the Inner London Education Authority in the 1970s. After her books became successful, she taught at several places, including Pennsylvania State University, at Rutgers University and at the University of California, at the University of Los Angeles and Illinois, among others. She was awarded the Order of the British Empire in 2005.

Willingness to write and improve her English

Graduation and small jobs were driven, from the beginning, by the desire to write, improve her English and your communication with the rest of the world. After several rejections, she received an opportunity as a columnist for the English newspaper New Statesman and there he began to write about personal experiences. The texts became the basis of the first book, In the ditch - 1972. Two years later, she published Second-class citizen.

While her first two novels have an autobiographical character with some fictional elements, the subsequent works have a tone of historical rescue, set against colonial Igbo Nigeria in the early 20th century. The Africa that his mother knew.

The joys of motherhood

In several texts, Emecheta expressed the need to communicate and alleviate anguish through writing. It is therefore natural to imagine her reaction to discovering that one of her daughters was going to live with her father. Devastated, she then wrote The joys of motherhood (1979), an openly ironic title. It was her book with the greatest repercussion and positive reception around the world. This book received its first translation into Portuguese in the TAG edition sent to club members in October. 2017. It was the first work by Emecheta published in Brazil.

Set against the backdrop of the same colonial Nigeria of the first half of the 20th century, the work narrates the trajectory of Nnu Ego, a young Igbo, whose choices will be guided by what is expected of a woman in her social context, being a mother. Once married, Nnu Ego realizes that she cannot bear children, one of the greatest disappointments and misfortunes for a woman of her culture. Her sufferings seemed endless until she finally gave birth; however, the conditions to support her children were increasingly precarious.

Life in Lagos, her new and urbanized place of residence, forced her to adapt for which she did not feel prepared. Her life was directly affected by the influences of the English colonist's culture, transforming the traditional values of her land of origin.

The mishaps experienced by Nnu Ego reflect a culture of violent patriarchal and colonial oppression. Buchi Emecheta reveals in her work the prison in which Nigerian women live and their clear position of subordination to men, both Nigerian and European, with different power relations, but always placing women in an inferior position in society.

With its ironic title, The Joys of Motherhood is often used as support material to discuss at school the weight of tradition's expectations on women and the changes introduced by colonialism.

Buchi's writing themes

Most of her fictional works focus on sex discrimination and racial prejudice based on her own experiences as a single mother and a black woman residing in the UK. Her autobiographical writing reveals a historical overview of the ills suffered by women during the neocolonialism that took place in African countries between the 19th and 20th centuries.

Themes related to child slavery, motherhood, female independence and freedom through education gained recognition from critics and several tributes. She called her narratives "stories of the world, where women face the universal problems of poverty and oppression, and the longer they stay, no matter where they originally came from, the more the problems become identical." Her works explore the tension between tradition and modernity. She has been declared the first successful black novelist to live in Britain after 1948.

Some of the published books

Novels

In the ditch - 1972 - chronicles the struggles of the young Nigerian Adah (Emecheta's alter ego), raising her children in the slums of London and her marriage to a London man. Her husband decides to return to Nigeria, but she refuses. The man then leaves anyway, abandoning his wife and five children. Adah then comes to depend on the welfare of the state and on dual jobs to survive and raise children.

Second Class Citizen (1974) - In Nigeria in the 1960s, Adah has to fight against all kinds of cultural oppression against women. In this scenario, the strategy to achieve a more independent life for themselves and their children is immigration to London. What she did not expect was to find, in a country seen by many Nigerians as a kind of Promised Land, new obstacles as challenging as those in her homeland. In addition to the racism and xenophobia that Adah did not know until then, she is met with an unwelcoming reception from her own compatriots, faces her husband's domination and domestic violence, and learns that second-class citizens are only expected to submission.

The bride price (1976) - Aku-nna is a young Igbo girl who sees her life crumble after her father's death. She needs to leave Lagos, along with her mother and brother, and return to the rural village of Ibuza, where she will face the anguish of adolescence and the rigid patriarchal traditions of her people. There, she falls in love with Chike, son of a prosperous family, but descended from slaves. This love is considered an affront to Igbo culture. However, the couple is willing to do anything to stay together, even knowing that this path can be tragic.

The slave girl (1977) - winner of the 1978 New Statesman's Jock Campbell Award, is a denunciation of the patriarchal oppression of women and their bodies, with Ogbanje Ojebeta as the protagonist, an orphan girl sold by her brothers to a relative away, after illness and tragedy left her orphaned as a child. Her fellow slaves become, for her, a surrogate family. When she becomes a woman, she feels the need for a home, a family, freedom and identity and only then realizes that for this she must choose her own destiny.

Destination Biafra (1982) - the first book to present a woman's perspective on the Nigerian Civil War.

Autobiographical works

Head above water (1984; 1986) - as for my survival over the last twenty years in England, she says, from when I was in my early twenties, dragging four cold babies and pregnant with my fifth - it was a miracle. In addition, if for some reason you do not believe in miracles, please start believing, because I have had to keep my head above water in this indifferent society.

Kehinde (1994) - the plot revolves around a woman who, after living in London for sixteen years, is forced to return to Nigeria with her husband. The resulting conflicts in their lives reflect the experiences of many women in the modern African diaspora.

Many of her novels revisit the same themes and draw inspiration from her life. There is perhaps no other African writer in whose works his own biography is as centered as hers is. Her work illuminates her life while her life confirms her work.

Books for children and youth

Buchi has also written for the children's universe, in projects for television and in an autobiography – which includes, among other stories, the origins of The Joys of Motherhood. Titch the Cat (Illustrated by Thomas Joseph; 1979). Nowhere to Play (illustrated by Peter Archer - 1980).

Her life and fiction feed into each other as her novels are often referred to as “fictionalized” accounts of her life. Although Emecheta was a symbol of the modern African woman, she rejected being called a feminist. If it were, she would have to be called a feminist with a lowercase 'f'.