I am my own heroine

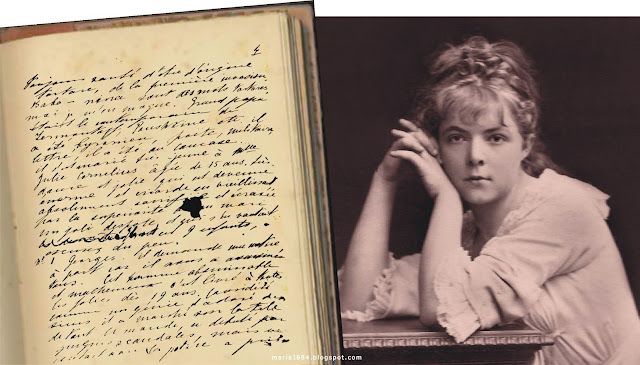

In May 1884, an unknown young woman named Marie Bashkirtseff staked her desire for fame on the publication of her personal journal. She knew that she would have little time because of advanced tuberculosis. Her right lung had already been damaged, while his left was slowly deteriorating.

She wrote what would become the definitive version of

her Journal's preface to the point: she wanted immortality, by any means

possible. If she had enough time left before her death, she would want to gain

posthumous renown through her painting. In case of premature death, her journal should be published.

She failed, despite her efforts, because she was not

part of literary or artistic circles at the time; she did not even come out of

an illustrious line of poets or painters. Russian gentry, her maternal family

had left what is now called Ukraine in 1858, touring Europe with the family

doctor and a retinue of servants. At fourteen, she started writing her Journal.

Desire for glory and fame

She elaborated in detail the means by which she aimed

for glory and fame. First, she tried to achieve celebrity through her voice,

consulting with singing masters in Nice, Paris and Rome, imagining herself

feted on the stages of Europe. Chronic laryngitis, probably the first symptom

of the tuberculosis that would end her life, nullified this aspiration.

In her Journal, she wrote long, glowing descriptions of

her face and her nudity, passing this undue attention to herself as a grandiose

gesture toward posterity. She slyly remarked that she would be spared the

trouble of talking about her physical appearance.

In front of the mirror, she described herself in the

act of admiring her "incomparable arms", the whiteness and delicacy

of her hands, or the shape of her breasts, effectively transforming the pages

of the Journal into places for the exhibition of her physical appearance that she

could not show in public.

Letters sent to famous writers

Anonymously, she first wrote to Alexandre Dumas Son

(illegitimate son of the writer Alexandre Dumas), author of The Lady of Camellias. In 1883, she sent

letters to Émile Zola, a 19th-century French writer and one of the leading

writers of French naturalism, author of Germinal,

The Experimental Novel, and The Human Beast.

Likewise, she contacted Edmond Goncourt, French writer, author of an intimate journal, novels and plays. In 1884, he published Chérie, a novel he had first announced in his preface to La Faustin in 1882. Describing it as "a psychological and physiological study" of a girl's first steps toward womanhood, he solicited what she called "female collaboration," directing her readers to jot down their teenage memories and send them anonymously to his editor.

With her characteristic bluntness, Marie informed him

that Chérie was full of inadequacies.

She said that she herself had been writing her own impressions from an early

age and now proposed to send them to him. Whether Goncourt received the letter

no one knows; if he did, he did not respond.

In 1884, months before her death, she and Guy de

Maupassant, a French writer and poet, exchanged nineteen letters that years

later were revealed through the press. Many people has been speculated about

whether the painter and the writer met and, around this hypothesis, the most romantic

hypotheses were woven.

Undaunted by her lack of success in inscribing herself

into the lives of literary greats, she promptly wrote their names in her

preface. The Journal's value as reading material lay, she asserted, in its status

as a human document: the public had only to consult Messrs. Zola, Goncourt and

Maupassant. It was an exaggeration, as she well knew.

The Journal, her last attempt to go down in history

Now I do not just write at night anymore, but also in

the morning, in the afternoon, in all my free moments. I write as I live. Marie

Bashkirtseff, Journal, Wednesday, April 5, 1876.

I see a very strong relationship with the Japanese

writer Higuchi Ichiyô and the Brazilian Carolina Maria de Jesus, whose journals

were published. The Japanese writer was also a victim of tuberculosis and died

young, at the age of 24.

Marie wrote her Journal without sketches, without a

first draft of the work, even the drawings are almost absent there, although it

is quite natural to fill in the lines with illustrations when you know how to

draw. There are also no corrections, so frequent in writers, after meditating

on the sentence.

She takes care of the purity of her Journal like an oral

job, but treated as a serious job. The characteristic feature of the text

signed by her is that it is charged with spiritual energy, unlike so many

others who die as soon as they see the light.

When Marie Bashkirtseff's Journal appeared in France in

1887, published by the publisher Fesquelle for its prestigious collection

Bibliothèque Charpentier, this first two-volume edition was an editorial

success.

In its pages, it fully exposes itself: I, as an object

of interest, may be very insignificant for you, but imagine that it is not me,

imagine that this is a human being who tells all his impressions since

childhood. It will then be an extraordinary human document.

Her feelings, her reflections, her contradictions, her

remorse, her humility, her joys, her extreme narcissism, everything,

everything, since her adolescence she entrusted the reader with more than

nineteen thousand manuscript pages that in the complete French edition

published between 1995 and 2005 covered sixteen volumes.

The Journal earned the aspiring painter the fame she so

craved, but she did not get it in life. It was one of the first attempts by a

woman to secure celebrity through personal brand curation – and the shape she

shaped female ambition in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the next post, we will deal exclusively with her Journal. The publications and the repercussions generated after her death.

Literature, your innate gift

As for writing, she said more than once that it was

her innate gift, an activity she did not have to struggle to study for, as it

had to do with music or painting or as it should. She confesses that if she had

had time, a less limited life, she would have dedicated herself to journalism

or Literature.

A trunk in her quarters held dozens, perhaps hundreds,

of draft articles, plays, and novels that she never had time to tackle or

finish. The chronicles she left in his Journal about the stories of his trip

through Spain or the art reviews she wrote for La citoyenne the death of Léon

Gambetta, a French republican political leader who helped direct the

defense of France during the Franco-German War of 1870 – 1871, testify to its

literary power.

The search for recognition through naturalistic painting

At nineteen, her ambitions became more focused. In

1877, she joined the Académie Julian

in Paris, the atelier for European girls with serious artistic ambitions whose

gender prevented them from entering the École

des beaux-arts. She worked doggedly, spending long hours in the studio

during the day and at night, calculating in her Journal how many months it would

take to catch up with and surpass the studio's most talented students.

Marie stood out for the social meaning she wanted to

give to her work, this reflection, we can think, of her commitment to the new

political conceptions she had embraced and which very likely made it possible

for her to understand the painful reality of those defenseless beings she chose

as models.

As a painter, she enrolled in Naturalism, the literary

and artistic current that defended an authentic vision of the reality of the

time. She painted the humble beings of the Paris suburbs. She met the young

Jules Bastien-Lepage, leader of this current, to whom she was united by a friendship

that was accentuated with the illness and the proximity of the death of both.

In 1878, when she was still in her early months at the Académie Julian, at the Paris Salon, he presented his much-discussed painting Les foins (Hayfields), the first in a

series of works that would make her a star and guide for many young painters of

the time.

These times were the turning point between traditional

painting that still captured historical or mythological themes or beautiful

girls and naked angels and the new currents, among which Impressionism was

already thrashing in full force.

Bastien-Lepage's work is a peasant couple taking a

midday break, and there the realism of the image leaves little room for beauty

as understood by academic painters.

Marie, impressed by the rawness of naturalism in the

work of Zola or Maupassant, Daudet and Flaubert, must have been drawn to

Bastien-Lepage's naturalistic painting.

Five years later, at the Salon of 1883, she presented

three works. She had all her expectations fixed on the oil painting Jean et Jacques, two kids on their way

to school. The jury, however, gave her an honorable mention for a pastel, the

portrait of her cousin Dina, which plunged the artist into deep irritation.

With Jean and Jacques she makes her debut as a

naturalist painter when, in the conservative eyes of the jury, a placid,

minor-genre pastel portrait more appropriately fitted the archetype of a

respectable young artist. Marie hung the honorable mention from her dog's tail

and it looks like the jury never forgave her.

From 1883 onwards, among the few works by Marie

Bashkirtseff that have not disappeared, we have two other testimonies of her

commitment to Naturalism: The Umbrella,

one of the many girls who sheltered the asylum next to her house, on Rue Ampère

de Paris and housed the children Jean and Jacques.

The painting won her the acceptance of the public and

the critics, with which she hoped to get the long-awaited medal. However, the

Salon jury, perhaps still offended by the rudeness of the previous year, and

demanding on the subject, turned their backs on her.

Devastated, she could no longer paint because of

illness and because the attempt to deliver her Journal to a talented executor

such as Maupassant or Goncourt had failed, she mustered her last energies to

console her admired Jules Bastien–Lepage, a naturalist painter, who was also

dying. An unexpected altruism took the place of the egomania that dominated her

life.

Aníbal Ponce,

Argentine thinker and essayist, noted: from

that moment on, the last pages of the Journal are lit up with the glow of

twilight. Until then, Maria Bashkirtseff knew only ambition: since that visit,

she has known kindness.

Feminism and the lament for the feminine condition of her century

Perhaps it is now difficult for us to understand how

much contempt there was in that (disqualification at the Paris Salon), the

election of Marie Bashkirtseff, in a universe in which even women themselves

accepted their role as secondary protagonists — mere spectators most of the

time. The right to vote was just the tip of an iceberg of limitations,

prohibitions and submissions that the stronger sex imposed so naturally.

Women had no civil rights, a decent young woman could

not propose marriage, every young man could and should lead a life of levity,

but a respectable girl had to be a virgin, a young artist could not address

transgressive themes... Marie Bashkirtseff regretted this with a game of

consonances, l'honneur et le bonheur

(honor and happiness) as he shed disconsolate tears over the death of his

admired Leon Gambetta, republican leader: what

I cry now... could only describe it correctly if it had the honor of being

French and the happiness of being a man.

She lived with Parisian high society by joining a

socialist feminist association. There she promoted and funded the creation of a

newspaper in which she excelled in another of her great vocations, journalism.

If, in the classical sense, tragedy is the death of

the hero, in that memory revered by its readers, Marie Bashkirtseff's unhappy

epic was its main substance. "I don't chapter," she once wrote

standing up, pen and brush in hand, like a mythical Amazon facing the evil that

would take her to her grave.

At the moment when a new feminine paradigm emerged -

exactly the one that today's women defend - to inaugurate the rebellion against

a world dominated by men who instituted marriage as their only and immemorial

destiny, the girls shuddered with the battles of this fragile girl who she

fought her crusades deploring the feminine condition of her century.

Used and suggested links

Writing about Marie Bashkirtseef requires a lot of research and condensation for the limited space of this blog. This text was based on the blog Diario de Marie Bashkirtseff del José Horacio Mito.

He discovered Marie Bashkirtseff as a youth in Buenos Aires in the 1970s, reading the Journal, a yellowed edition he found in one of the many legendary second-hand bookstores on Avenida Corrientes.