Loneliness far from home

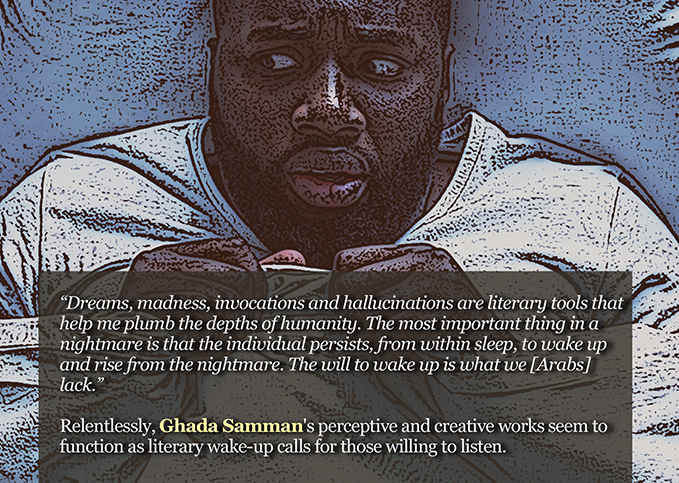

Ghada Samman is a prolific writer who has produced over 40 works in a variety of genres including journalism, poetry, short stories and romance. She was born in 1942 in Damascus, Syria. Outspoken, innovative and provocative, Samman is highly respected in the Arab world, albeit at times controversial. Several of her works have been translated from Arabic into English, French, Italian, Spanish, Russian, Polish, German, Japanese and Farsi.

Her mother, also a writer, died when she was a child and she grew up in the care of her father, a university professor, dean of the University of Damascus and cabinet minister. She claims it was her father who fostered within her an appreciation for hard work and learning.

Young Samman chose to pursue a BA in English Literature at the University of Damascus rather than medicine, as her father had hoped. She then obtained an MA from the American University of Beirut, where she wrote her thesis on the Theater of the Absurd.

From there, she went to London to do a doctorate, but ended up abandoning the project. Her father died while she was in London. During that pivotal year of 1966, Samman also lost her job as a journalist for a Lebanese newspaper and was sentenced in absentia to three months in prison for leaving Syria without official permission. The sentence was later overturned on a general pardon by the Syrian government. At the time, however, Samman was completely alone, an unusual position for a young Arab woman of her social class.

Samman willingly traded the personal freedom she experienced in the West for a sense of belonging to the Arab world. She chose to reside in Beirut because, according to her, it seemed to allow a certain degree of freedom within the Arab world and embody the battle between enlightenment and oppression. During the war in Lebanon, Samman resided in Paris for about 15 years with her husband and son. Today, she maintains two houses, one in Beirut and one in Paris.

The Arab Spring and the wars in Lebanon and Syria

between 1975 and 1990, Lebanon went through a bloody civil war, involving Christians of the Phalanges’ Party, Muslims of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Israeli Jews. The conflict emanated from the deterioration of the Lebanese state and the agglutination of militias that provided security where the state could not. These militias formed largely along the following communal lines:

Lebanese Front (LF), led by the Falangist (or Falange), represented Maronite Christian clans whose leaders had dominated the traditional elite of the country's sociopolitical fabric. The Maronites are part of a Catholic religious order that recognizes the Pope as the head of the Church. The institution originated in Lebanon, through Saint Maron, a hermit who lived until about the year 410 and who is preaching achieved the conversion of many people;

Lebanese National Movement (LNM), a coalition of secular leftists and Sunni Muslims sympathetic to Arab nationalism. Sunni Muslims are the members of the group that recognized Abu Bakr as their successor and follow the precepts of the Islamic religion according to the Quran and Sharia. They also base their beliefs on the Suna, a sacred document that chronicles Muhammad's experiences. The word Sunni comes from Ahl al-Sunna, or people of tradition. Tradition in this case refers to practices based on precedents or accounts of the actions of the Prophet Muhammad and those close to him. For this group, religion and the state should be a single force. Their religious leader is called the Caliph. Sunnis consider themselves the orthodox and traditionalist branch of Islam;

Lebanese National Movement (LNM), a coalition of secular leftists and Sunni Muslims sympathetic to Arab nationalism. Sunni Muslims are the members of the group that recognized Abu Bakr as their successor and follow the precepts of the Islamic religion according to the Quran and Sharia. They also base their beliefs on the Suna, a sacred document that chronicles Muhammad's experiences. The word Sunni comes from Ahl al-Sunna, or people of tradition. Tradition in this case refers to practices based on precedents or accounts of the actions of the Prophet Muhammad and those close to him. For this group, religion and the state should be a single force. Their religious leader is called the Caliph. Sunnis consider themselves the orthodox and traditionalist branch of Islam;

Amal (Hope) also an acronym for the Afwāj al-Muqāwamah al-Lubnāniyyah (Detachments of the Lebanese Resistance) movement, comprising Shia populists; and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which represented Lebanon's large population of Palestinian refugees. Shia is a sect of Islam, which means supporters of Ali. Shias consider Ali Bin Abi Talib (cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad) to be the legitimate successor to Islamic authority. The Shia sect considers the Sunnis, who took over the leadership of the Muslim community after Muhammad's death, to be illegitimate. Their religious leader is called an Imam.

War in Syria

The Middle East and North Africa region was rocked by a wave of anti-government protests that became known as the Arab Spring, which began on December 17, 2010 and ended in mid-2012. The War in Syria began in 2011, when there was a series of protests against the government of Bashar al-Assad. The war had a major impact on a civilian population estimated at over 24 million people in the first five years. Unfortunately, it is not over yet. In some cases, such as Libya, the country's top leader was removed. The same did not happen in Syria.

The war started after the allegations of corruption revealed by WikiLeaks. In March 2011, protests took place south of Derra in favor of democracy. The population revolted against the arrest of teenagers who wrote revolutionary words on the walls of a school. In response to the protest, the government ordered security forces to open fire on protesters causing several deaths. Disgusted by the repression, protesters demanded the resignation of President Bashar al-Assad.

The opposition armed itself and fought against government security forces. Brigades formed by rebels began to control cities, countryside and villages, supported by Western countries such as the United States, France and Canada, among others.

Both sides of the conflict imposed a food blockade on civilians and the interruption or limitation of access to water. On several occasions, humanitarian forces were prevented from entering the conflict zone. The Islamic State took advantage of the country's fragility and launched itself to conquer important cities in Syrian territory.

Survivors reported that harsh punishments such as beatings, gang rapes, public executions and mutilations were imposed on those who did not accept their rules.

Characteristics of Samman's Writing

The same drive for individual freedom and free expression of thought that guides Samman's personal life also characterizes much of her writing. As a journalist, she explored aspects of Lebanese life that were largely ignored by ideas, attitudes or activities considered normal or conventional, namely the plight of the poor in neglected areas of northern and southern Lebanon. Refusing to submit to social or literary conventions, Samman established her own publishing house in 1977. Thus, she was able to publish her own writings without editorial interference.

Whether in her relatively early romantic writings or in socially engaged fiction like Beirut '75. Samman's work displays a boldness that defies any restraint. Although her writing sometimes feels repetitive, her interesting blend of surrealism and verisimilitude, along with her mastery of the Arabic language, allows her to be simultaneously poetic and political in her prose writing.

Magic realism

Samman's ability to appropriate non-Western literary traditions for specifically Arab contexts is best illustrated by employing an Arab type of magical realism in The Square Moon, a collection of supernatural tales set in realistic contexts.

In this collection, Samman explores the difficulties and internal contradictions experienced by many Arab immigrants living in Europe. In settings far removed from their origins, the various characters find liberation for women, but also racism, displacement and alienation. As they struggle with issues of identity, loyalty, separation and personal freedom, they also discover the tenacious hold of old traditions over their lives that appear in many forms, some positive, some negative.

Through symbolism and allegory, Samman addresses sensitive social and political issues that can be very dangerous or less effective if confronted directly. A distinctive feature of her work is the symbolic use of animals to give insight into the human condition.

Symbolic Use of Animals

In her book Beirut '75, the turtle and the performing monkey are the only figures who react with fear to the intimidating sound of Israeli fighter jets as they break the sound barrier above Beirut. The instinctive and natural reactions of the animals provide relief against the indifference of the Lebanese people, who ignore both the portentous warnings of threatening planes and the worsening socio-economic and political situation.

The turtle, who plays the shadow of Yasmina, one of the main characters, is able to “come out of her shell” in the novel and find “wings” to fly through the window of Yasmina's apartment in search of freedom.

Unlike the turtle, and more like the characters themselves, the colorful fish hanging from a vendor's stall in Beirut's popular market district can only escape their transparent prisons through a desperate attempt at death. Samman makes this point poignantly when Farah, Yasmina's counterpart in the novel, compares herself to the fish when she realizes she is "trapped inside a glass jar" only to witness one of the bags containing the fish open, "sending its contents and splashing on the sidewalk.”

Beauty and horror store

Perhaps the strongest symbolic use of animals in Samman's works is found in Beirut Nightmares. The pet shop, which the writer, narrator and protagonist visits repeatedly both in dream and waking, comes to function as an extensive political allegory, recreating in microcosm the socioeconomic and class conditions in Lebanon at the beginning of the war.

The difference in the physical appearance of the pet shop's entrance and back exposes the superficial, hypocritical and exploitative aspects of pre-war Lebanon. The store entrance is reserved for customers. It presents a beautiful, modern, clean and urban environment. The protagonist sneaks a glimpse into the back of the store, which reveals the cramped, dirty and horrible conditions in which the storeowner keeps the animals.

Like the poor and oppressed Lebanese masses, the animals remain in appalling conditions to ensure the commercial success of the pet owner, whose wealth depends not only on the mistreatment of his animals, but also on his presentation of a convincingly modern and progressive model that can be seen at the entrance to the store.

Confusion in the face of freedom

Like the underprivileged Lebanese masses, the animals in the pet shop have become so used to prison that they are lost and confused when the protagonist opens their cages and offers them freedom. So, like many of the Lebanese fighters waging war on the streets of Beirut, the animals turn on each other long before they attack the shop owner. When the man finally remembers to bring food to his charges, the dogs attack him.

As we can see in these examples, Samman's use of the symbolic is not just firmly anchored in concrete socio-political and historical conditions. It also participates in the world of fantasy and the surreal. This style, as several critics have noted, is similar to the fantastic realism developed by important Latin American writers such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Isabel Allende.

As Samman reveals in Register: I am not an Arab Woman, the ghosts in The Square Moon are of a different variety than the gothic or Hollywood type of cinema. They are not limited to palaces and the rich, nor do they wear white sheets and burst out laughing. Instead, they take forms modeled on those found in Arab folk superstitions and literary traditions.

The Parisian swan that bewitches the Arab protagonist of The Swan Genie has specifically Arab qualities. Nicknamed “Smart Hasan” by the protagonist, the swan recalls the tales of his grandmother, “Arab myths” and the “tower” from “The 1001 Nights”. Through these means, Samman highlights the ways in which his use of magical realism is specifically Arabic, not only expressing the concerns of this people but also drawing on Arabic literary precedents.

While Samman's use of the supernatural is most consistent in The Square Moon, it can also be seen at significant moments in each of the three books on the Lebanese Civil War. In a mysteriously prophetic moment in Beirut '75, a minor character, a soothsayer, declares, "I see a lot of pain and I see blood - a lot of blood."

In the apparent fulfillment of the fortune teller's prediction, the nightmares in Beirut Nightmares often take on a supernatural aspect, as the protagonist's flights of fancy blur the distinction between her waking and sleeping states, allowing her to see, hear, and report on aspects of Lebanese life that even the fortune teller in this second book is afraid to pronounce.

Indeed, the protagonist's insistence on recording and rescuing her manuscript is itself a Schahrazadian movement, an attempt to prolong her life by telling politically engaged but fantastical stories in the face of an apparently imminent death.

In Laylat al Milyar (The Billion Dollar Night), the wizard's mysterious incantations go back to the witches in Shakespeare's "Macbeth”, but they also find their source in a specifically Arab superstition and the use of magic still practiced in certain parts of the Arab world. Her magic, along with her own psychological breakdown at the end of the novel, allow for the symbolic representation of the various characters' inner feelings and desires.

Negative reviews

Unconventional in both her personal life and literary works, Samman is undaunted by the negative reviews that some of her works have received. She portrays “taboo” themes such as political corruption and female sexuality and exposes everything she considers hypocritical, exploitative or repressive in Arab societies. To that end, she creates strong but flawed characters in specifically Arab sociocultural settings, and relies heavily on stream-of-consciousness, symbolism, allegory, and fantasy in much of her work.

Escape from the clutches of your unbearable reality

The implantation of the surreal in all these works is successful thanks to Samman's use of the nightmare motif. Beirut '75 ends with a series of nightmares for Farah, which seem to function as a release from her madness, which is itself an escape from the clutches of her unbearable reality. In a highly absurd gesture that combines introspection with self-assertion, the novel ends with Farah replacing the sign announcing the entrance to Beirut with a sign that reads Hospital for the mentally ill.

Beirut Nightmares picks up where Beirut '75 left off. The title and chapter titles, along with the grotesque comedy, the absurd and the macabre, all recreate the nightmare aspect of civil war, suffocating experienced by the protagonist narrator in her waking and sleeping states.

The recurring fantastic excursions that are the protagonist's nightmares function as a literary device, allowing for variations in the scenario of the action. In addition, they are a forum for political criticism and questioning of topics as diverse as corruption, inequality, the plight of the poor, and the role of violence in the revolution, and especially the relationship between the pen and the gun.

In one of the many Kafkaesque repetitive episodes, the absurdity of war is portrayed in the situation of the protagonist's brother, whose attempt to flee the confines of his front-line apartment lands him in prison for possession of an illegal weapon.

The final book in the trilogy, Laylat al Milya, reveals how Samman's characters seem to have "fled from the nightmares of their homeland to discover the nightmares of exile". Moving the action from the confines of Beirut to Europe, Samman exposes the ways in which so many Lebanese emigrants manage to recreate, in exile, the same socio-political conditions of exploitation that perpetuate the war in Lebanon.

In Beirut '75, the inner madness experienced by Farah triggers the “nightmares” sections of the book. In Nightmares of Beirut, the external madness of the war around her traps the protagonist in a nightmare world of dreams and political reality. In Laylat al Milyar, drug-induced hallucinations evoke a surrealistic world, which in turn reveals the nightmarish real-life conditions of the characters. We see it through the eyes of Khalil, who is coerced into becoming a drug user.

In a semi-hallucinatory state, Khalil is taken to a “circus”, where he watches various surrealist “shows”. In one, people live in a cage whose roof descends imperceptibly but safely over its sleeping occupants. When Khalil tries to warn one of them about impending disaster, he is told to mind his own business.

In another “show”, poor revolutionaries invade a gilded cage only to replace its rich occupants and assume their positions as they sit in their seats. In this circus world, the police have the function of silencing or expelling anyone who speaks out against the show. The participating women are satisfied with traditional female roles and refuse any alternative to their daily household chores.

The “common man” refuses to take responsibility for his fate, certain that only “what is written” will happen to him. Others fall to their deaths, jumping into a pool that proves to be just a mirage, as onlookers watch them, unwilling to warn them of their misperceptions because they are “of a different religion” than theirs.

It is easy to see how the different episodes in the circus represent the sad state of Arab, and especially Lebanese, life as Samman sees it. It is a state of forced silence and voluntary surrender, a state far removed from the glories of Arab civilization as epitomized (and idealized) in the Andalusian Arab past, a time and place in history to which one of the stunted circus performers allows Khalil to travel in the secret time.

Notes of Hope and Triumph

Despite their nightmarish atmospheres, Samman's works inevitably end on a hopeful note. Beirut Nightmares ends with the promise of a new life, symbolized by the flaming rainbow that the protagonist sees in the Beirut sky after she manages to rescue herself and her manuscript from her apartment.

Laylat al Milyar ends on a similar note of hopeful triumph symbolized by the colorful kite that flies over the Beirut skyline despite the bullets aimed at it. Moreover, Khalil spies the kite as he returns to the city with his two sons.